Welcome to Weed Church. All Are Welcome.

First, a word.

Jesus said, "The man old in days will not hesitate to ask a small child seven days old about the place of life, and he will live. For many who are first will become last, and they will become one and the same."

-Gospel of Thomas, Saying 4

This week I studied Yama.

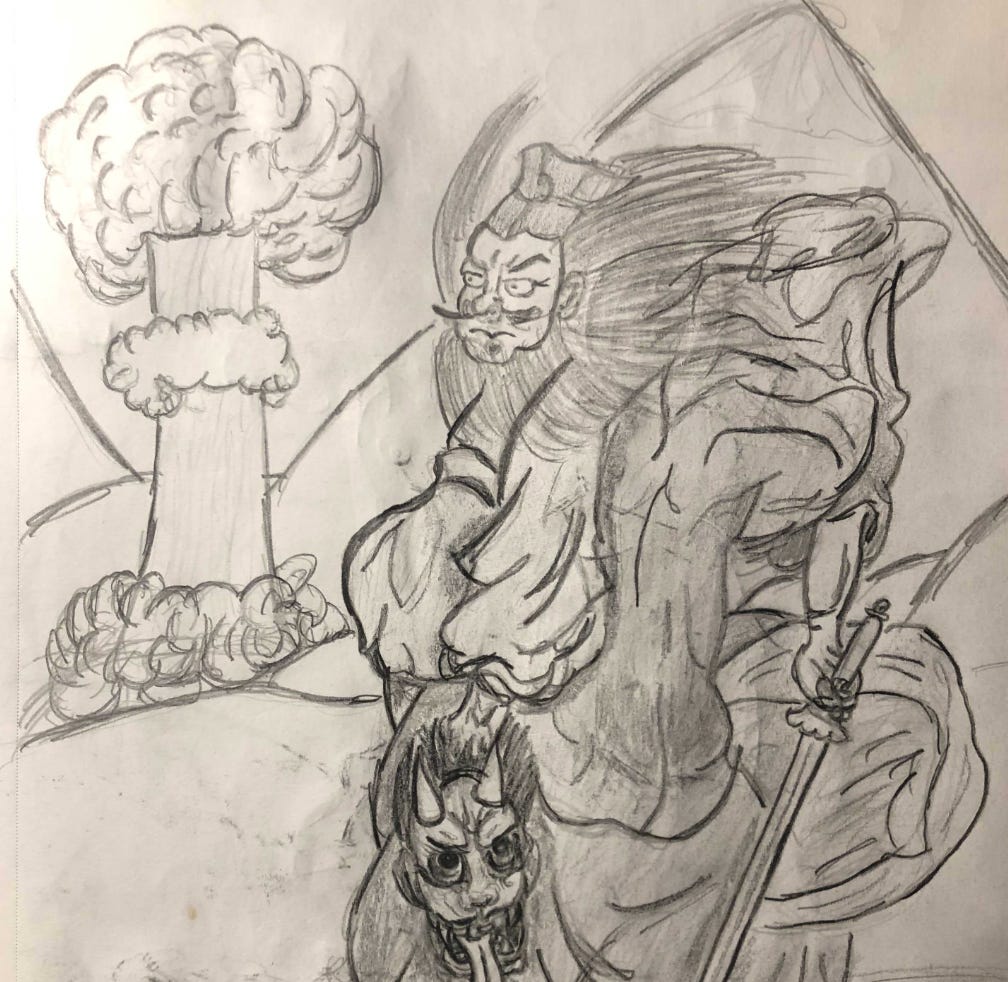

Yama can differ by culture and practice. The protector of Dharma and ruler over the realms of Hell, Yama is a greedy but fair ruler. Unlike the devil, Yama will let you earn your way out of hell.

He can be many things, but the icons preserve the essence. His eyes wild with brows flaming and snub snout open wide, fangs curled and forehead adorned with five skulls as a crown. His third eye is front and center on a big fat head, rolled upward in bliss, his mouth open for whatever else he can slide in his gullet.

Yama sits atop splayed corpses, sometimes riding on a bull. He carries a weapon; a flaming sword or a skulled club. He is the manifestation of many of our worst qualities. Yama is clinging and controlling, and if you owe he’ll send you back to hell until you pay up.

College students are children.

It is easy to forget that, particularly in a country where many of them are allowed to sign up to go kill people in Somalia, but it is true. They are children. They are not especially educated, yet. That’s why they’re in college: to get more education.

Many of them are very smart. “Smart” is useless these days. Clever, sure, but smart? Smart’s stock has completely tanked. What’s the point in being smart when one can look anything up at any time? Probably better to be clever, so one knows which stuff matters and can avoid getting bogged down with stuff political scientists talk about or stuff that journalists write about that is, by the by, completely useless to the average person in any practical sense.

Because all of it only works once one has gotten clever enough to know what to ignore and what to listen to. When you’re a child, that’s much harder to do, because one probably doesn’t know what life is going to look like yet. They are exiting a period of extreme nurturing in many cases, or at least a period of more nurturing than they will experience when out on their own. Even the least supportive household is still a roof.

How is a child expected to navigate the decision of choosing a path towards personal and spiritual satisfaction while also weighing financial terms they’ve never been exposed to? What responsibility does a society that will undoubtedly benefit owe this child?

As currently constructed, the answer is debt. We owe this child less than nothing. In fact, this child owes us. They owe us for the privilege of improving their mind, something that our society demands of them in order to achieve a semblance of comfort or happiness. They owe us for the privilege of learning things that we force them to learn to achieve dignity. They owe us for putting up with their shit for eighteen years.

There are counters to this. Trade school. Blue collar labor. Associate’s degrees. All the things that adults like to say are on the table for the indebted children. Student debt is a choice brought on by the decision to acquire a Bachelor’s or advanced degree has, until recently, been the general mantra in our country. But it’s an imaginary choice. It’s coerced by the American Dream we’re fed via mass media and observed institutions; two cars and a garage, kids, a dog, a healthy social life: these things are expensive. A child doesn’t learn the real cost of a given path until they’re grown and it’s too late to unravel the balance sheet they’ve acquired to that point.

I was 21 the summer my dad threatened to kick my ass. We were delivering the mail together. I was good at it, for whatever that’s worth. Being good at delivering the mail may not sound like anything to brag about, but it requires a certain affinity for pain, or a numbness to the repetitive nature of existence. That comes in handy later in life. You practice on the mailroom floor, setting your route up in a tiny crate as clerks bring pile after pile of mail over to you, all of which is unorganized and corresponds to a little 1 inch vertical slot with a number and street name on it. You finish a crate and another shows up. You do that until you’re done, and sometimes you’re the last one there, and you get out and sweat your balls off and empty the truck.

Tomorrow you do it again.

So when the postmaster told me I’d make a great career mailman and my father was in earshot, I was informed later what would happen if I were to take the postmaster up on his offer. My father was a gentle man who never put a hand on me, so this was not some outburst but a rather measured statement. At that point, he’d been delivering the mail for 15 years and he carried those 15 years in his legs and shoulders, jutting this way and that as he shifted his body to compensate for whatever joint was on fire that day.

I don’t begrudge him anything. In fact, I wonder if I do owe it to him to see it through. Even after everything I’ve seen that conflicts with my own sense of morality. Even after realizing on the other side of it that it was an unavoidable scam. A sort of moral ponzi scheme.

First, consider my father’s position. He was living the “noble” blue collar life, knew it inside and out, and came from it in his childhood. His father was a public school teacher, and my dad told me they ate a lot of pork chops growing up. You carry that kind of shit with you. Even during the decade that my father had created a temporary comfort with us selling insurance, we never experienced much lavishness because my parents both knew how quickly it could all collapse. The Taylors were in the hole. The Taylors still are. We might get out of it this generation, but it’s still up in the air.

I struggle with the memory of that summer because delivering mail is still the job I look back on with the highest degree of fondness, but at that point I also was realistic enough to know that my dad was right. I was pot committed. I was probably $40k in the hole by the end of sophomore year. I don’t tell a lot of people I went to Carnegie Mellon University because as soon as I do, they assume I’m a rich kid and usually say “oh, computer science or business?” and then when I say no, writing, they say “I didn’t know Carnegie Mellon had a writing program.”

Well, first of all, yes you did, because it’s a college and all colleges have an English department. So, what you’re really saying is I thought the smart kids there knew how to make a buck and that’s not exactly incorrect either. I would catch myself feeling dumber than hell in my 20s when I realized that writing for money was as self-indulgent a pursuit as getting an MBA, considering the shit you had to eat to do it. I don’t regret it in the way I don’t regret being born. I wasn’t meant for it and thus didn’t pursue it. Still, when you end up in marketing anyway for a little while, you start wondering why you felt the need to cosplay integrity as a teenager.

I remember at 19 it being first time that I was surrounded by people whose parents could write $60,000 checks with enough advanced notice—3 weeks or so, give or take. I knew wealth existed when I was a child, as I was smart enough to get into Carnegie Mellon, but I had assumed that everyone in the suburbs was like my family. Faking it, basically. A lot of them were, but Carnegie Mellon was the first time I was exposed to the prevalence of those that weren’t faking it at all. The billionaire class is obvious because of its scarcity, but the millions of people that are liquid in ways that ~75% of Americans can never even conceive of. That was eye opening. That’s why I didn’t really question my dad when he said he would go up side my head if I dropped out. Aside from the fact that I was pretty sure he could still kick my ass at age 60-some, or at least do enough damage that both our asses would be at the doctor. He’s from Uniontown, and those boys are different.

Maybe that’s just rationalization for why I still enjoy my job as a researcher. I don’t really think much about it, because I’ve got three kids that need healthcare, and I work for a very good company run by a good guy, as far as that stuff goes. There’s a lot of bad shit out there. I avoid it. I write when I can. I read every day. I practice maitri as often as I can, and I am honest with myself about transparent delusion, even if it appears to be delusion at a mass scale.

Because so much of this life is delusion; the same unavoidable scam that drove me to seek prestige education at the behest of “being something greater” in the eyes of my parents. It’s for that reason that I’m also trying to shed so much of what I used to value or want while avoiding the trap of nihilism that has claimed so many people I know and love. Nihilism is such an easy trap to fall into, particularly during dark times, but it’s a false bottom. It’s just as easy to make everything have meaning as it is to deny meaning to existence, both a dullard’s point of view. I’ve forced myself through it, impossible to believe in a lack of meaning when surrounded by the eyes of children.

If I am to break the cycle of hell for the Taylors, for whatever cosmic offense we are repaying Yama for, it must be through a path of cynical warmth. My father showed me Maya when I was young; his excessive joy at delivering the mail for a fraction of what he made selling people insurance showed me material success was a false god. I admired the way he channeled his salesman’s desire for competitive argumentation into being a bulldog of a shop steward at the post office. Despite that, his insistence that I pursue something spiritually greater was a reminder that Thina—or sluggishness of will—is also a grave obstacle to happiness. To aspire to repetition is the opposite of liberation.

One of the gravest crimes one can commit is to disrespect their elders, but tradition is of the heart rather than the flesh. And the status of elder is earned, not given, as even Yama is not immune from punishment in his own realm of hell. I don’t owe it to my father to live the American Dream as he pictured it, but I do owe him a life that pursues hopefulness rather than nihilism.