The End of the Thousand Year Reign

Arminian Baptists, Ethiopianism, and the Birth of Rural Vanguard

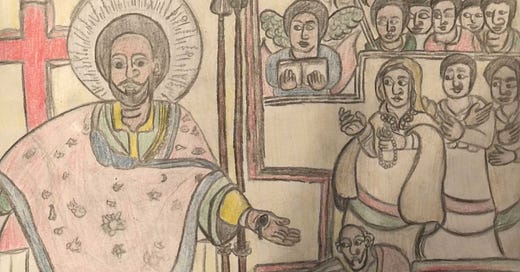

THE ETHIOPIAN BAPTISTS OF JAMAICA

The Baptist Wars were fought in Jamaica in the 19th century, though you’d be forgiven for thinking there was only one. The first, beginning on Christmas of 1831, started out as a peaceful protest organized by enslaved Baptist preacher Samuel Sharpe, and eventually turned into the largest slave rebellion in Jamaican history. Fourteen white people were killed, and in turn the Anglo colonial government killed a few hundred Africans while putting down the uprising, and then executed another 300+ for good measure afterwards. Sharpe was among those executed in the aftermath, and the government response to the rebellion led to inquiries largely credited with the abolition of slavery in Jamaica in 1833. Sharpe, for his efforts, is now on the Jamaican $50 note and was declared a national hero in 1975.

Sharpe was continuing and escalating the work of another important man who is not yet one of Jamaica's seven national heroes–though some have argued for his inclusion. George Liele was an emancipated slave and Baptist minister who brought the faith to Jamaica in either 1783 or 1784. He called it the Ethiopian Baptists of Jamaica, an early expression of Ethioipianism, which would become one of the defining philosophies of Jamaican liberation. “Ethiopian” was itself something of a misnomer brought on by the poorly translated 1611 edition of the King James Bible, applied by abolitionists to slaves because of the Kingdom of Abyssinia. Historian William Scott wrote in 1978 that many if not most Black people in the United States moved on from “Ethiopian” by the 1830s, worried that African identity could continue to hinder assimilation for emancipated Black people after decades of intellectual debate about repatriation to Africa. Nonetheless, Ethiopianism thrived in the Caribbean while sputtering in the United States, largely because of the difference in demographics: the English ran so much human trafficking through Jamaica that the tiny island rivaled the entire landmass of Brazil–itself a playground for Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and English slavers–and thus Africans outnumbered Europeans by a ratio of 5:1. Ethiopianism thrived because, unlike the United States and its pockets of Africans in a largely European nation, Jamaica’s African population had numbers.

What they didn’t have, up until Liele arrived, was an education. And the way that Liele went about securing that education is ultimately what complicates his legacy: he played a very political game within the Anglican social structure, ultimately seeking to humanize the African people within the colonial society rather than seeking violent revolution. This is not to imply that his work was well-received. It took many years of lobbying the Jamaica Assembly–itself an extension of the English imperial project, Jamaica having been an English colony since it was captured from the Spanish in the 17th century–before the government finally agreed that all who wish to worship God were allowed to do so freely. Before long, Liele was preaching to more than 1,500 enslaved Africans on the island and providing those with permission from their plantation owners with an education. Liele himself had enslaved people that he bequeathed to his wife when he died (with instructions to liberate them that his wife ignored), so this was not exactly a figure that sought active liberation but one who, in the Anglican tradition of respectability politics, clearly modeled a system of penance before salvation. His participation and respect for the system didn’t matter much in the end to the Anglos, who slaughtered hundreds of Black men, women, and children in the first Baptist War, which erupted just three years after Liele died.

It’s not fair to judge Liele’s method of liberation relative to others, and not just because of time and contextual circumstances surrounding his strategy. Rather, the result of the first Baptist War all but validates that initial approach—albeit unseemly, both in hindsight and at the time (Liele had detractors who accused him of collaborating with the English). Liele had to fight just to get permission to speak with slaves and teach them about finding their own path to God–the seed of all mental liberation–and even after decades of organizing and community building the rebellion was swiftly and forcefully put down. It’s easy to judge Liele’s participation and meek approach, but even easier to imagine how swiftly his mission would’ve ended had he arrived in 1784 preaching Ethiopianist apocalyptic liberation from the start.

Samuel Sharpe, by taking action, took the next step in Jamaica’s evolution as an independent nation of African people by introducing forceful resistance: the Baptist War started as a peaceful protest of working conditions for enslaved workers. The protest only escalated when the Anglican elite on the island sought violent retribution on those who dared join, erupting into the rebellion that would forever change the course of slavery in the Western hemisphere. The first Baptist War was a mere month after another Baptist preacher, Nat Turner, had been executed in Virginia for leading one of the most famous rebellions in American history. The Baptists were becoming a problem.

Thirty years later, about six months after the American Civil War reached its bloody conclusion, a second Baptist War in Jamaica broke out under another name: the Morant Bay Rebellion led by Baptist deacon Paul Bogle, another of Jamaica’s seven national heroes. Like the first Baptist War, Bogle was leading a reasonably peaceful march in protest of living and working conditions for Africans on the island. Slavery had been abolished for three decades, but much like the American south after the abolition of slavery, Black men and women were forced to live in squalor and excluded from participation in community affairs. Similarly to the first Baptist War, the outcome was slaughter so horrific that London was forced to act once again, the brutality of its colonial governments consistently stretching beyond the furthest reaches of even the depraved mind.

The difference in this Second Baptist War née Morant Bay Rebellion is that it was not the Ethiopian Baptists, but the Native Baptists, a group that arose out of schisms caused by George Liele’s controversial approach. Never mind that Liele was himself charged with sedition and nearly arrested or executed multiple times, it was apparent that his arrival with the Tories and friendly relationship with the English—political as it was—put a ceiling on just how much trust he could earn among the enslaved Africans on the island. The Native Baptist movement, contrary to the hierarchical and somewhat political Ethiopian Baptists, were a bit more anarchic in nature; in theological academia, the Native Baptists are what is known as an Arminian Baptist movement. There are two reasons why this relatively niche label of Arminian is important to understand:

Arminian Baptist movements at the time preached what’s called “substitutionary atonement,” which encouraged people to find individual harmony with the Holy Spirit and God. This stands in stark contrast to Wesleyan Baptist movements that were a bit more focused on what’s known as “Governmental theory of atonement,” which basically states that if you are true to God you won’t ever be punished because God already did that to Jesus. Arminians were encouraged to find their own path to God, with hierarchies discouraged and all having an equal channel to the Holy Spirit.

Arminian Baptists had no central governance. In the modern world, this is actually quite a hindrance and one of the reasons why the evangelical movement in America has turned into such a horrifying grab-bag of bigotry. But 200 years ago, if you were an enslaved or emancipated African who had been granted freedom of worship, a church with no central governance was an advantage. It meant that, under the cover of Sunday worship, the oppressed could gather and discuss the scriptures in ways that related to their life experience in the fields and mines. It’s where the story of Moses and the book of Revelation became more than apocalyptic warning, but an inspirational vision of the reckoning at the end of the 1,000 year reign.

The Baptist link is so much more than mere coincidence, though, particularly framed against the philosophy of Ethiopianism that was driving so much rebellion. In Ethiopian Tewahedo tradition, John the Baptist is nearly as revered as the savior Himself, the man Jesus describe as “whom none born of women were greater.” John the Baptist spoke the truth even in the face of great danger, all in service of what he believed to be right, himself earning the respect of Jesus Christ for his audacity and commitment to God; the Messenger of the coming King. For his efforts, John the Baptist got his head cut off.

Arminian Baptist movements like the Native Baptists of Jamaica were all over the antebellum south and often at the center of rebellion and controversy in the communities where they thrived. Henry Highland Garnet, friend of American abolitionist John Brown and Presbyterian minister, spent time in Jamaica with the Native Baptists before falling ill and returning home to continue preaching and fighting for abolition in the United States. The story of Caribbean Baptists is also the story of Antebellum Baptists: a gradual reckoning of a shared past and ancestry, a reclamation of a theology that had been part of African heritage from the beginning, and finally a solidarity movement among the rural peasantry who realized that the math was on their side. Baptist theology was syncretized with Nigerian spiritualism in some areas of the Western hemisphere. The removal of the academic-like hierarchy of an Anglican, Catholic, or Presbyterian institution allowed the enslaved people to find their own path and expression of God, unbound by the flawed interpretations of their oppressors.

Before Maosim formalized it into the modern language of political science a century later, it was Ethiopianism that helped establish the revolutionary bonafides of a rural vanguard among the peasantry. Although, for theological geeks, it’s a little difficult to separate the two philosophies, given the overlap in development between the Ethiopian Tewahedo Church and the Church of the East. And the Tewahedo influence would only grow: while the phrase “Ethiopianism” would start to fade, a new and extremely recognizable movement in the West—albeit for largely racist and commercial reasons, as most things are here—would rise from the death of its last prophet. In the 1890s, a Baptist preacher started a Black power movement so revolutionary it would lead to the rise of a new savior in the Caribbean, the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, coronated in 1930. Before his coronation, he was known as Ras Tafari.

BEDWARD AND THE CRUMBLING OF THE WALL

The Pharisees and Sadducees are the white men, and we are the true people…There was a white wall and a black wall. The white wall was closing around the black wall, but now the black wall was stronger than the white wall, and must crush it. The Governor is a scoundrel and robber, the Governor and Council pass laws to oppress the Black people, that take their money from their pockets and deprive them of bread and do nothing for it.

-Alexander Bedward, 1895 (as quoted in Chevannes, 1971)

The bones of The Jamaica Free Baptist Church on August Town Road are still standing, the guts and ceiling long removed so that Alexander Bedward could finally ascend to meet God. All that’s left are the cornerstones laid in 1894 and the walls that went up around them, the open doorways and windows and roof giving way to the near constant reminder of divine grace in the lush landscapes of the island.

It was here that Bedward warned of the “white wall” closing around Black Jamaica that would eventually destroy it; the “AntiChrists” in the Anglican church who used their power and influence to keep Black people subjugated, including the Black preachers within those established religions. Bedward preached a message of radical Pan-Africanism, a transition from encouraging Black men to understand their inherent worth in the eyes of God in an inherently oppressive culture to a more fiery scripture that raved about supremacy for God’s chosen people. Like Paul Bogle before him in 1865, Bedward wanted the Africans on the island to look outside of their colonial governments for inspiration; to aspire to more than just a functioning cog in the white European social order. The Second Baptist War was a rallying cry for Bedwardites and held up as an example of the inevitable outcomes of injustice against Black people. The tide had been turning not just in the Caribbean but in the United States, where the Baptist church was becoming a growing force in the Reconstruction era; the National Baptists Convention–not to be confused with the Southern Baptist Convention, which is the racist one–was founded in 1895 and is still the largest Black religious organization in the United States.

Before Bedward was a preacher, he worked the Panama Canal as a young man before receiving a vision from God brought on by anger at the injustice of seeing white men receive more money for the same work than Black and Indigenous workers. He joined the Native Baptist movement in 1888, hesitantly taking over as the leader of the church in 1893. Bedward preached a message of radical Black power to his congregation, using showmanship and fiery sermons against the white colonial government, encouraging disenfranchised Black people on the island to band together on the basis of their skin color as a show of solidarity. While Bedward’s work is theological in nature, you can start to hear the origins of the brilliant Walter Rodney in the 1960s, who would come to recognize the Caribbean as more of an African nation than an English or Western country. Bedward’s rhetoric was framed in the language of the time, but his “white wall” sermon is roughly equivalent to the observations made in The Groundings With My Brothers by Walter Rodney: if Jamaica was a nation with a ratio of five Black people to every one white person, then it was a Black nation that shouldn’t be ruled by a predominantly white colonial force.

By the end of the 19th century, the English government had learned its lesson from the last two Baptist Wars and didn’t put down Bedward and his emerging religion–the Bedwardites, an entirely new movement within the Native Baptists focused on Black liberation–with violence that would bring attention to its cruel practices. Instead, the authorities arrested Bedward for sedition and had him thrown in an insane asylum for his unorthodox preaching style and claims of being a Black messiah. Bedward clashed with another activist on the island, Joseph Robert Love, who founded the local newspaper the Jamaica Advocate. A Black newspaper, the Advocate was used as a political tool to advocate for incremental change and social reform for the Black working class and impoverished people in Jamaica. Love and Bedward would’ve been working towards the same goals in theory, but as a prominent member of the Anglican church, Love found Bedward and his followers to be beneath his politics. Much like the schisms between the Ethiopian Baptists and the Native Baptists earlier in the century, there was still active political dispute between how the descendants of African people on Jamaica should pursue liberation–change from within a system, or dismantling a system that would rationalize something as horrifying as slavery in the first place.

Bedward was eventually placed in an insane asylum for good when he failed to fly to heaven from a tree he’d climbed, where he would die in 1930. As was usually the case, the spectacle of the tree distracted from the fact that the arrest and forced placement in an asylum was as much political as it was out of concern for Bedward. The Bedwardites were going to march to Kingston to do battle with the elites over conditions in the rural areas of the island. Bedward was no fool or deluded psychopath, but another advancement in the theology of liberation in the West. Bedward gave the Black men and women in Jamaica permission to pray not just in a different way than the colonial government and Anglican elites, but to a completely different version of God.

It took decades before Bedward received his due as a prophet rather than a lunatic, whose primary grounds for insanity were recognizing and speaking plainly about the conditions he and his people were facing. By preaching Black supremacy and about a Black Christ, he encouraged his followers to look beyond the white wall that had formed around them and remember that this, like everything else, was temporary. That the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice, as we were reminded by Dr. King (himself a Baptist). It’s odd how often in the West, acknowledgment of reality is treated as something fantastical.

One of Bedward’s followers, Robert Hinds, was the right hand to Leonard Howell, and together they helped found the Rastafari movement. Soon, they were preaching and evangelizing just like Bedward to growing crowds of Black men and women about the King crowned in Africa instead of a crucified European Christ. Ras Tafari was coronated after many years of speculation and international acclaim, now known as His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie, the Lion of Judah, Emperor of Ethiopia; according to Howell, he was the one prophesied by Marcus Garvey. To true believers, Selassie was not just the dawn of a new era for the motherland, but a literal reincarnation of Jesus Christ.

The divinity of Selassie is a fascinating subject to consider, albeit one that can be considered heretical and therefore is hotly contested. As with all symbols in religious movements, the question is just how literally one takes the words of the scripture, both in the past and present interpretations of them. While there are many Rastafari who would still bristle at the suggestion that His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie is anything less than a Christ reincarnate, there is also the original interpretation of the Christological doctrine of the Ethiopian Tewahedo Church; the one that ultimately caused the first big schism in the Great Church after the crucifixion. It feels absurd to speak about 2,000+ year old theology with any sort of urgency, but the schism over whether Christ was a human God or a human who achieved unity with God is a remarkably big deal. One of these things–which is the belief of the Catholic Church and therefore nearly all of Western Christianity–implies that an omniscient God reached down from somewhere and put a baby in the womb of a virgin. The other, which is the foundation of Ethiopian Christianity, is that Jesus Christ achieved divinity by working to match his material existence with a perfect and divine spiritual essence. It’s the difference between actively seeking retribution and justice for the Earth in the Tewahedo tradition, and hoping someone else figures it out in the European one.

It’s in this sense that Selassie’s divinity is up for theological debate–as the crowned African King with supposed Solomonic lineage, Selassie could be interpreted as the culmination of centuries of restoration, as many Rastafari did–but given the current condition of the world it also feels somewhat irrelevant. Selassie the symbol is many things, but the man has a complicated legacy marred by horribly mismanaged famine and tribal wars and it’s pretty clear that we have not yet arrived in paradise. His critics point to this mismanagement as inherent evidence against his competence let alone his divinity, but believers (of which there are still many) would argue the Lion of Judah didn’t realize who he was getting into bed with when trying to manage Ethiopia’s place in the fraught relations between West and East during the Cold War.

Retrospective analysis of anyone’s life and legacy is complicated, particularly in a nation like Ethiopia that evidently has more history of civilization than any other. Perhaps those who debate Selassie’s literal divinity miss the forest for the trees, as many who get bogged down in scriptural and semantic debate do. Whether Ras Tafari was prophesied ruler today in the 21st century is less relevant than what he meant 100 years ago to men and women like Bedward, or Bogle and Sharpe before him, who had themselves already spent more than a century and a half rewriting a religion that was stolen from them in the first place; weaponized as the tool of imperial conquest. His Imperial Majesty Haile Selassie and the stories of Ethiopia’s many victories—against the Italians, in fighting for African Unity, in bringing Western leaders like Churchill to his knees with awe—further cemented Selassie as a material reminder that the bleak history enslaved Africans had been force fed by Europeans was a lie. Selassie was more than an African Christ figure to those who had been ripped from their homeland by the West, but the aspirational symbol of man’s innate desire for liberation.

Alexander Bedward had to climb a tree and hope that God would lift him into the air high enough to see the collapse of the thousand year reign on the horizon. Can you see it still, closer now than before?

Casey Taylor is a writer manufactured in southwestern Pennsylvania and West Virginia.