Welcome to Weed Church. All are welcome.

First, a word:

So they set out, until when they came to the people of a town, they asked its people for food, but they refused to offer them hospitality. And they found therein a wall about to collapse, so al-Khidhr restored it. Musa said, "If you wished, you could have taken for it a payment." - Quran 18:77

And as for the wall, it belonged to two orphan boys in the city, and there was beneath it a treasure for them, and their father had been righteous. So your Lord intended that they reach maturity and extract their treasure, as a mercy from your Lord. And I did it not of my own accord. That is the interpretation of that about which you could not have patience." - Quran 18:82

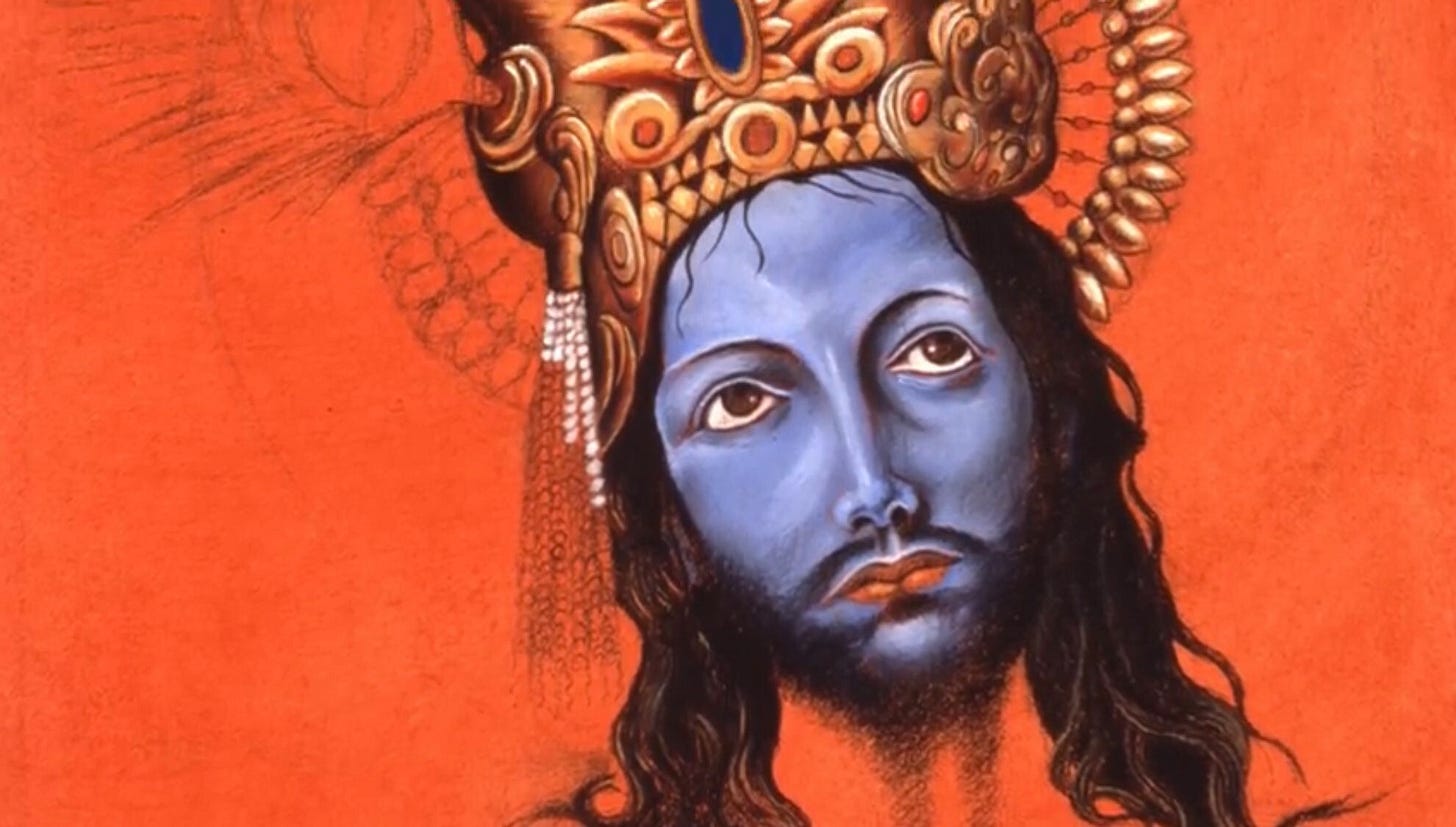

al-Khidr

al-Khidr is the giver of life, but he’s not the creator. He has no name, yet he is present in tales from the Vedic era through Islam and onward. He is The Green One.

There is a distinct difference between the giver of life and the creator. Anyone can create. Anything can create, as the modern marvels of industrial efficiency on our assembly lines or in our artificial intelligence algorithm churn out soulless products for mindless consumption. Creation is the bare minimum. Creation is pathetic.

Life is given through something greater than creation; something less tangible. al-Khidr’s most notable parable is that of the encounter with Musa—Moses here, Musa always, like the great Musa Mwariama, the Moses of Kenya who slaughtered British colonizers that tried to destroy the Mau Mau–but this Musa is the Musa of parting the Red Sea. And his encounter with The Green One–sorry, al-Khidr or, sorry, I mean St. George (it can get so confusing!)—was not necessarily a joyous one. Musa watched as al-Khidr sat idly by atrocity after atrocity with minimal concern or drive to intervene. Why? Because al-Khidr understood something Musa never could. None of us are in control of any of this. All of this is only as real as we want to make it. Musa sought liberation but was confused when faced with its ultimate manifestation in The Green One, who understood that liberation was not about fighting, but about making sense of one’s impotence in the face of the great chaos.

There are more joyous al-Khidr tales that illustrate the same concept. Like when he was imprisoned with nothing but a dead branch and, from his cell, created a thriving garden of the branch that was so powerful it spilled through the cell and broke open the prison. al-Khidr didn’t bother leaving. Why would he? It was his garden.

I feel so bad for the literalists that can’t make sense of this kind of stuff. I feel so bad for everyone all the time, but I can’t tell them that, or they think I’m being judgmental.

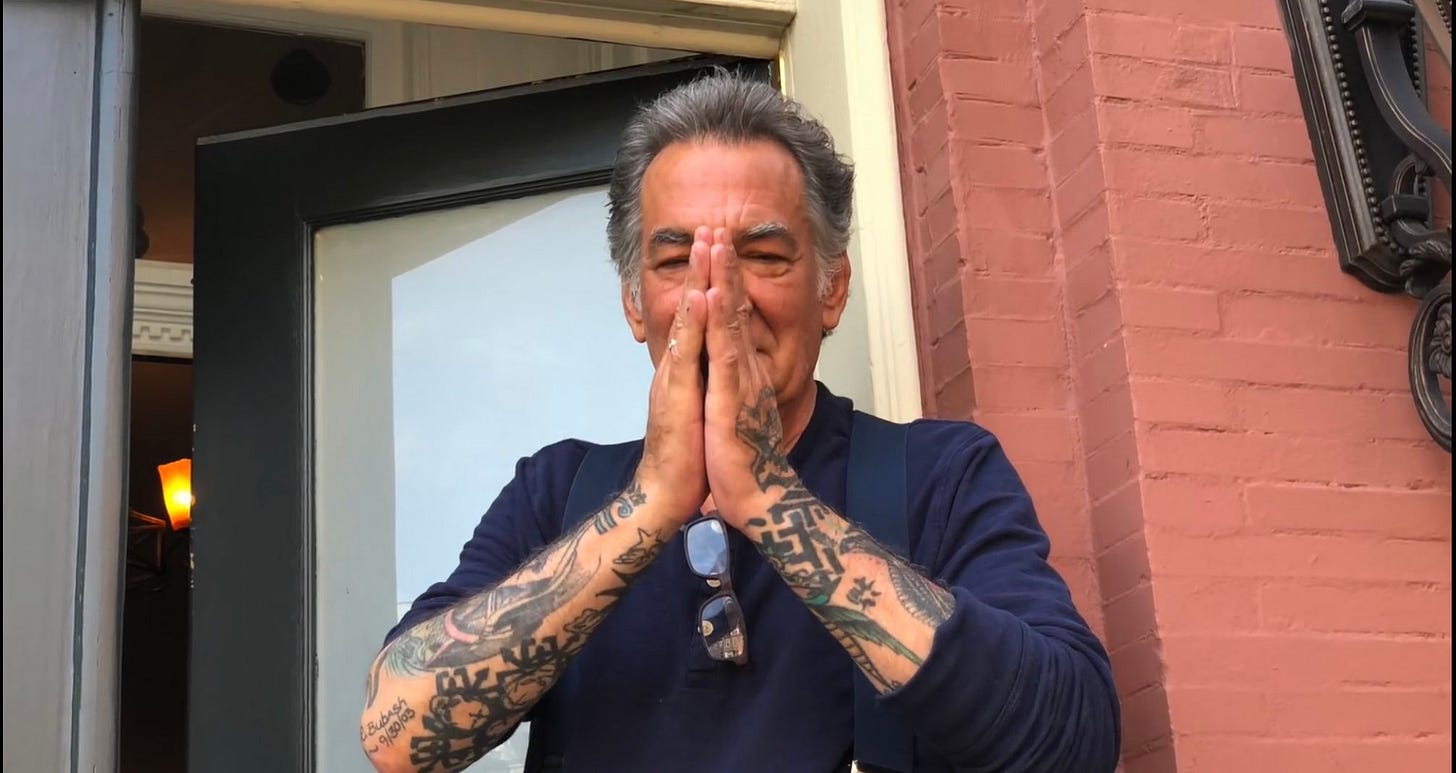

I Miss My Friend Nick. Happy Birthday Nicky.

The Queen died the day after Nick Bubash’s birthday, but Nick wasn’t here to see any of it. Goddamn, I wish he was. I wish he was here all the time. I wish we could watch the West collapse together.

I met him in Crafton last year for a piece I was writing for Defector. The piece was going to be about Hardy, mostly, until I met Nick and realized that the story was so cosmically different than I’d ever even considered that I had no choice but to rewire my entire brain. I went into it thinking I was going to write a fun piece about the first ever tattoo convention, when Hardy and Malone and Sailor Jerry and others welcomed Kazuo Oguri from Japan for one of the most important subcultural information swaps in history. Hardy ended up in Japan after, tattooing with Yakuza as perhaps the first ever Western white person to do so, boutique tattooing exploded after a slow burn for the first few decades, and the history of the movement has never been the same.

That was the legend. And it’s not exactly untrue. But Nick Bubash is a bit of a thorn in the side of the clean, sweeping individualist narrative that we love so much in the West. The one that says we owe it all to Hardy, even as we acknowledge that we owe it to others, too. Maybe that’s how it’s always going to be here. I don’t really care much anymore, given the way credentialed social credit has lost its luster these days. Nick didn’t either, for what it’s worth. But after I spent time with him, the story took on a life of its own. In fact, framing the story from the perspective of Hardy–the Western Anglo that brought other tattooing styles to America–started to sound a little offensive, given that we had the least history of all.

I never would’ve thought of it that way without Nick. I owe him everything.

It’s hard to summarize what I admired about it, I guess, but in retrospect I think it’s the way Nick refused to make the whole story about himself, something he had the credibility to do. One thing that’s important to remember about tattooing, and particularly old school tattooing, is that it was largely descended of carnies and self-promoters. As such, tattooing was often an art of bluster and character building on the business side, and someone like Nick had the kind of legendary resume that could leave one petty. Hardy was the household name, after all, and the man who had built himself an empire off of an aggressive self-promotion machine. That’s not to deny his talent–there is not nor will there ever be another Ed Hardy–but to point out that the man has written multiple autobiographies. When the greatest tattooer in the world also owns the world’s most respected tattooing publishing business, you start to wonder how organically the legend is building.

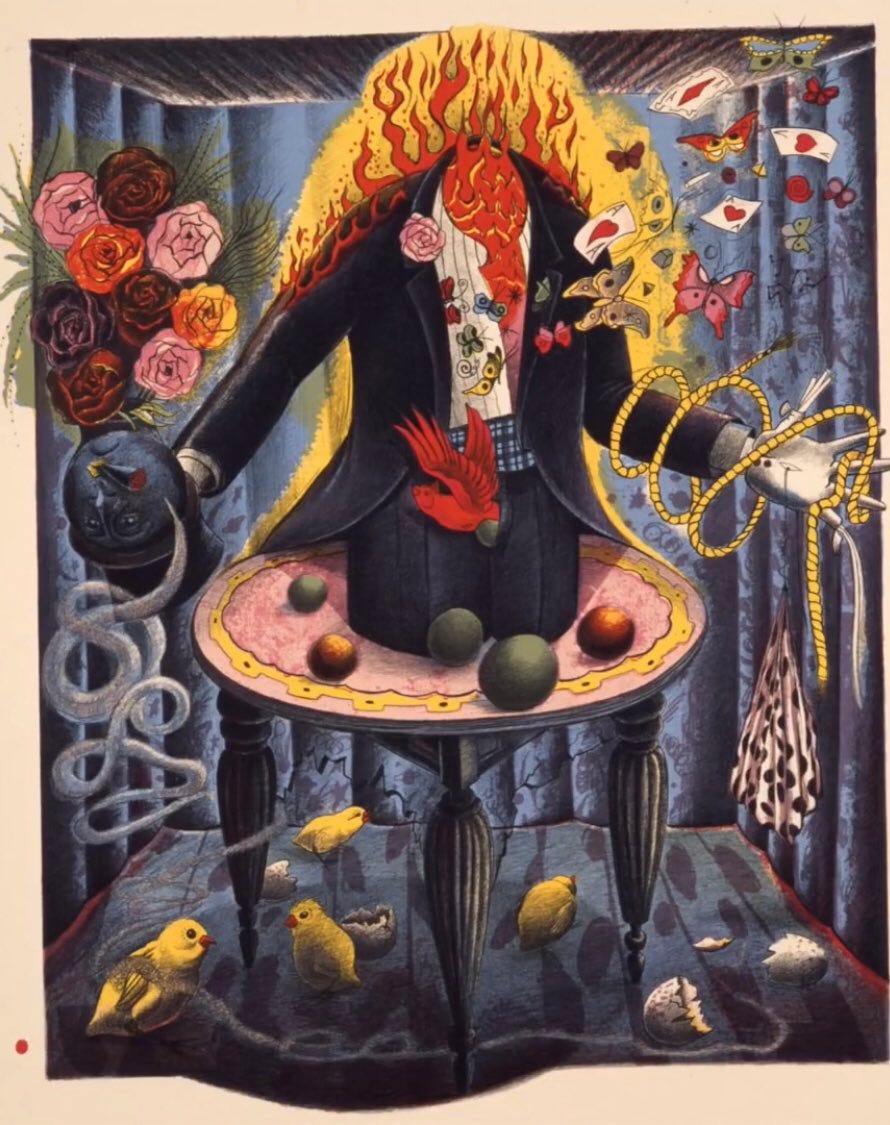

Nick didn’t give a shit. He joked about it the same way I’ve heard every older tattooer joke about Hardy getting all the credit, but he went out of his way to talk Ed up, to discuss how much he admired his focus and his practice. It was more powerful to listen to it that way against the backdrop of what was completely unspoken but understood: this man was every bit as good or better than Hardy, with even greater bonafides in the legit “high art” world, but it was Hardy that was inaccessible because of his celebrity. Nick Bubash was alone in a studio in Crafton fashioned out of a gutted and yellowed hair salon for blue hairs, the chairs and hair dryers replaced by sculptures of hideous monstrosities pulled from his imagination. The walls adorned with sketches and paintings of tricksters and hustlers, deities and saviors, Christ and the Lord Shiva. Nick walked me through all of it, his thought process, his craft, all the while interrupting himself to ask me questions about stuff I’d heard of, eyeing me to see if he could catch a hint of recognition. I’d never met a genius before.

It was when we started talking about New York that everything changed, that the beatnik from deep within Nick started to pull itself out of the shy, reserved Pittsburgh boy who would rather make fun of his own ambition than acknowledge his influence. But it wasn’t really about New York, because New York sucks–but about the New York that used to exist, perhaps only in his mind, perhaps only in the apartment where he learned from and worked with Thom DeVita, one of the greatest artists of the 20th century. Hardy was tattooing’s first celebrity, and the guy who got to charge thousands for tattoos while traveling the world, largely because he’d created enough buzz for his new style of tattooing that he could set absurd prices to compensate for the demand on his limited schedule. On the other side of the world, Thom DeVita was making signs for his tattoo shop that said “Tattoos Need Not Be Expensive” to mock Hardy, and wouldn’t allow Nick to charge more than $25 per tattoo because Thom charged $30.

They tattooed the working class. Thom tattooed the bodega workers and bus boys. Nick tattooed the gang members and burnouts. The Lower East Side where they were tattooing would be unrecognizable to anyone who pictures the New York of Giuliani and later, back then the neighborhood was mostly a burnt out safe haven for junkies and artists. Nick himself struggled with heroin addiction, which he finally kicked before going to art school at DeVita’s behest. Nick was too fucking good to keep tattooing cartoons, something that DeVita knew but didn’t want to push him toward too hard, lest he activate the unavoidable Southwestern Pennsylvania rebellion instinct.

I don’t know how you summarize a life’s work, so luckily an artist’s work speaks for itself. Nick’s work after art school and after he went to live in India is some of the most remarkable I’ve ever seen, melding influences and cultural references that span Appalachia to the river Ganges, all with a deep reverence and vocabulary for the Vedic. Nick spoke often about the craft of art, and while he never said it directly I recognized much of the thinking from my own Zen and Buddhist practice. An artist is supposed to do everything. A painter can paint, a designer designs, but an artist doesn’t stop at mastery because assurance is death.

Tattooing was something he couldn’t escape, a way of feeding his vices and paying bills as gambling replaced heroin as his addiction dujour. Nick was open about his addictions. He talked about them like someone would a problematic child–annoying as all hell, but hey, what the fuck are you gonna do? You’re stuck with ‘em. He talked about tattooing the same way, like the original unconditional love of his life, but he was always more interested in putting together a sculpture of the latest nightmare in his head, or assembling pieces he found at a junk shop into cryptids about the American ethos.

He loved Thom DeVita so much. It doesn’t capture it appropriately to say that he saw Thom as a father figure. Fathers are simply the creators. Thom was so much more to Nick; so much more to poetry. Nick gave me advice for my art and my practice that he got from Thom. I hear it every morning when I have my coffee and the kids start bounding down the stairs to interrupt whatever dumb thought I’d convinced myself was meaningful. But Nick’s voice is there in my ears and he’s saying what Thom told him, and it sets me straight.

I’ll never tell anyone everything that Nick Bubash told me on the night I visited him in his Crafton studio. It’s not that I think I’m the only person he ever told–as a non-tattooer, I’m fully aware there are things he likely didn’t and wouldn’t ever tell me until I was on the other side of that line–but that I worry that I don’t know what he told me that he didn’t tell anyone else. I don’t know what is privileged and what isn’t. But I like to tell people some things, if only because most people I meet (even those who like tattoos) don’t know who Nick Bubash is. And they don’t know who Nick Bubash is because Nick didn’t want them to know, because Nick didn’t seem to care much as long as he was able to do the work he wanted to do. The work will draw the people worth talking to. The work will speak for you. All other speech is bluster, posturing, cosplaying. Speech from the human mouth is the most useless form of communication there is; the most disposable and instantaneously forgotten. Anyone can talk.

Language is inherited and iterative. None of this is ours. Nothing belongs to anyone, least of all the words and symbols that we inherit from the ones who come before us. Nick taught me that it’s our job to take these things–this symbolic alphabet of words and icons and art and philosophies and incoherent esoterica–and meld them into something that makes more sense than what was left to us. Not to create order from chaos, but to observe the way that chaos has its own natural order.

We talked for hours about the continuum of knowledge, something that Nick learned from an uncle of his who was an academic that never stopped reading books, most of them history and poetry, diving through sequential rabbit holes like a detective on some cosmic case. Tattooing was that for Nick, the way it is for everyone who takes it seriously and seeks to understand its origins. The ultimate expression of folk art, permanent markings of the melting pot’s legends and figures and images that are often subterranean or unfit for mass consumption.

Nick didn’t bring any of this up in a self-serving way, but it became clear that I’d been thinking about my story wrong because I’d been thinking about the world incorrectly. I’d tackled so much wrongthink in my personal life and my own ego, but hadn’t considered doing so by confronting the biases of a Western world insistent on creating meaning and history where there is deficit. There was no story about the great Ed Hardy heroically bridging the divide between Japanese and traditional American tattooing, because that story only exists in the books published by Hardy.

The truth is always more complicated. The truth is located in the continuum of knowledge, where Hardy only got his ideas from the Eastern art that made its way back home from the imperial drive of American manifest destiny. The truth is located in the skin of men and women in Pittsburgh or Crafton or Chelsea, where Nick and Thom were creating avant garde tattoos that would change the future of working class culture. The truth was in Gifu, Japan, where the great master Kazuo Oguri had the idea to reach out to Sailor Jerry for advice on swapping tattoo ink. As Nick Bubash insisted, there was only ever one Ed Hardy, but he was a benefactor; a unique talent standing at the confluence of forces far beyond his control. Hardy was the seer who built a brand while men like Nick Bubash inhabited an idealist form of the working artist.

I saw the great tattooer J. Adams last fall, meeting for coffee to talk about a project he was working on that overlapped with some of the research I was doing. It’s fun to get together and compare notes with artists you admire. It’s important to find inspiration in the work of others rather than their success. I sheepishly asked J. about Nick, who I hadn’t talked to in a month or so since he’d been traveling. In the summer, Nick had agreed to tattoo my back, and I’ll admit to being more than a little over the moon about the idea that one of the greatest American tattooers to ever live was willing to do a backpiece for me in his 70s. But we hadn’t started yet, and it seemed like maybe Nick was uncomfortable doing it. That was the day I learned that Nick had cancer. That was also the day that Nick died and the world got permanently darker.

I used to ignore kismet but Nick told me not to. Why J. wanted to get together that day of all days, why we would be talking about the man we both admired, why it would take a dark turn towards conversation about the bleak inevitability that faced a hero and mentor. Two hours after we finished our coffee, J. texted me to let me know that Nick wasn’t just sick but was teetering on the brink. I was able to relay a message to his daughters and wife that they read to him before he passed on, one of many that were flooding in to a man who had inspired so many whether they knew it or not. I don’t know if he heard it or understood it, but I know he got it.

Shortly after his death, another wonderful Pittsburgh tattooer named Nick Ackman was having work done on what would eventually be the Pittsburgh Tattoo Art Museum, where Ackman and his partner Jill Krznaric now tattoo and show off antique flash designs from tattooers of the early 20th century. Both knew Nick Bubash, both learned from him, listened to his stories. An electrician was there to install lighting and wiring for the display cases and Ackman saw a faded cobra on his arm. Where’d you get that, Ackman wondered. Turned out it was at Island Avenue Tattoo in McKees Rocks back in the 80s. The electrician got it from a guy named Bubash. He had no idea he got it from an artist, a shaman, a fine art superstar, a wandering nomad descended of a man who cured polio; that walked India after shooting heroin in Chelsea. The Patron Saint of White Guys Gone Tribal. To the electrician he was the local tattoo guy.

I still haven’t started my back piece, the space still reserved for a man who can no longer tattoo it. But I’ve been talking with some of Nick’s friends at Old Soul Tattoo in Canonsburg, where Nick almost spent his last days tattooing but ultimately balked (largely because he couldn’t smoke in an official shop on account of health regulations). I think I’ll have them put al-Khidr on there.

Bye Now. Have a good Sunday. All the best.

[I’m going to be taking a break from Weed Church for the rest of this month, most likely. I refuse to commit to anything in general because if something occurs to me I’ll write it, but I want to focus my writing time on finishing an initial draft of a project that I’m very excited about, that readers of this blog will hear more about eventually.]

Its speculated that one of the antecedents for al-Khidr is Utnapishtim, the Babylonian Noah.