I watched a movie I liked with my wife over the weekend and this is a free blog for inconsequential thoughts, so now you’re going to hear about it. I don’t get into movies like I did when I was a teen and in my 20s, but cinema interest is like riding a bike (you never forget your pretentious instincts). Why not dust off the old “movie dork” brain and write about a good flick every now and again?

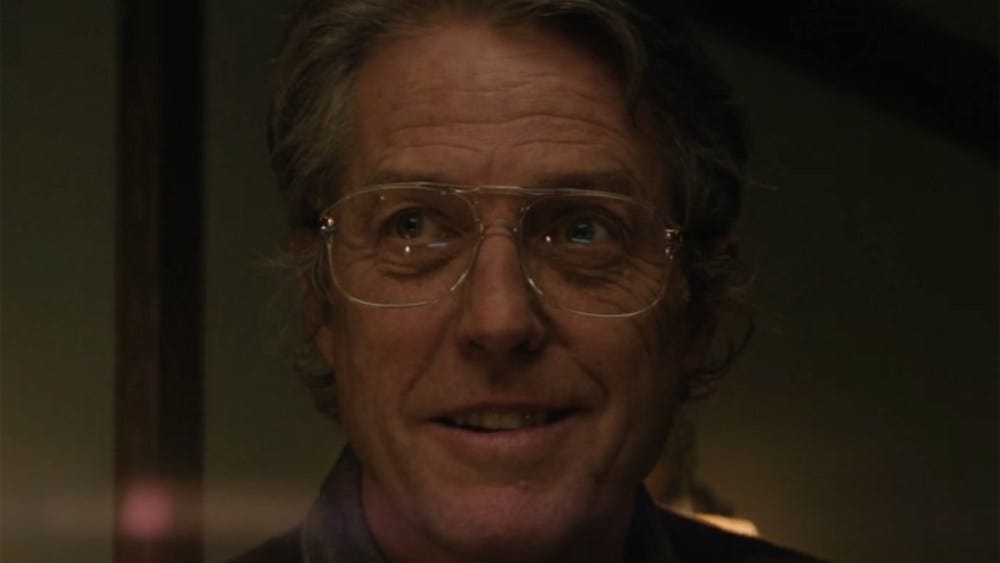

This weekend we watched 2024’s Heretic, an A24 psychological horror and tension builder starring Hugh Grant, Sophie Thatcher, and Chloe East. Thatcher and East play missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Mormons, for those seeking brevity) and Hugh Grant plays a lonely old psychopath who tortures them. Throughout the film, allusions are made to the relationship between hobbyist model building and the massive labryinthian structures man has built in the real world.

The allusions were subtle enough that it didn’t annoy me but persistent enough to let me know that this was a film about rat traps. As the film continued and Hugh Grant’s rat trap began to implode, it became clearer that the film was specifically about the difficulty distinguishing between a trap and a maze; architect and inhabitant.

In an Axios-style goal of succinctness (and not wanting to overwrite film criticism when there’s plenty online), here’s what I liked about the movie:

the performances

the way the writing depicted the LDS missionaries as young women first and Mormons second

the fun subversion of cat and mouse tropes

successfully maintaining tension even though it’s obvious that these gals are in for a bad time from the jump

There was stuff I didn’t like, too, but I don’t need to document most of that. The only pet peeve I feel strongly enough to type out is that the film does a nod to the “final girl” trope after Sophie Thatcher’s character gets Hugh Grant’d. The contraceptive implant was a clever plot device, but the final girl trope itself felt out of place in a film that critiqued traditional patriarchal views of “free will” when it comes to women.

[Also the reveal at the end was preposterous. I don’t care because movies can be preposterous but up until that point it wasn’t an especially preposterous movie, so the level of preposterousness felt like an escalation into tomfoolery. Tomfoolery is not my preferred zone, so I deducted points from my imaginary scorecard.]

I checked the Wikipedia for the movie after I watched it because I don’t really read film criticism (pretty busy), so that’s my way of simulating my teenage years playfully arguing in movie theater parking lots. I caught this review by McKay Coppins and I read it because I recognized his name because I think he used to be on TV or something. Maybe he still is. I don’t watch a lot of TV anymore.

The review is well written and very well considered. I’m not here to trash it (Coppins makes sharp criticism of atheistic bores), but I think that Coppins fell into the movie’s trap. Most of the negativity in the review is when Coppins makes sincere arguments against Hugh Grant’s absurd and grating sermonizing. For example, from the review:

“Just how seriously viewers are meant to take these ideas is open to interpretation. The character articulating them is, after all, a murderous psychopath. But the movie devotes considerable time to its villain’s ideology and seems to consider his diatribes provocative and sophisticated, even profound. Bryan Woods, who wrote and directed Heretic along with Scott Beck, has said that Mr. Reed is meant to have a “genius-level IQ.” It seems that we are supposed to think of Mr. Reed as brilliant but extreme—a man who, in the tradition of Marvel bad guys and Bond villains, takes a good point much too far. (Think of Black Panther’s Killmonger.)”

I strongly disagree with this perspective, and think the film makes quite clear from the gates that Grant’s character is a jackass with nothing interesting to offer. The teenage girls that he believes he is manipulating are always shown to be 1-2 steps ahead of him when he leaves the room, and are never once even slightly swayed by his tired and cliched criticisms of the LDS Church.

He’s a moron. Not only that, but the film quite clearly demonstrates many times that he’s a moron whose “scheme” is on track not because of his wit, but because he has locked innocent young women in his house and forced them to listen to his idiotic nonsense for his own entertainment. Coppins summarizes his feelings thusly: “In the end, the film doesn’t actually have all that much to say about Mormonism specifically.” This, too, I disagree with, but think that McKay Coppins may be biased by his status as a member of the LDS Church.

From the name of the film, it’s clear that the intention is to interrogate the idea of heresy, and those who become dedicated to heresy as a worldview. This is where I think Coppins may have missed the forest for the trees: Hugh Grant is the film’s nominal heretic, torturing devout young women over what he perceives to be the error of their faith, but the young women are also heretics. The LDS Church was founded on heresy, and Joseph Smith is one of America’s most notorious Christian heretics. Ever read up on the Vatican’s views on Mormonism? The film is not attempting to “platform” Hugh Grant’s absurd Wikipedia-level interrogation of faith. The whole thing is an in-joke for theology geeks; an inception of heresies within American Christian heresy.

In fact, if I felt like going deep, I could probably put together a convincing academic-sounding argument that Hugh Grant’s character represents the corruption of America’s founding principle of religious freedom. Grant’s character pushes the type of heresy one can find in “respectable” texts by British Orientalists a few centuries ago, only made possible by the Reformation. These Orientalist writings informed Masonic philosophies, and buddy, aside from Jehovah’s Witnesses, the LDS Church is about as Masonic as it gets in American homegrown Christianity. Grant is American religious freedom personified, wherein his curiosity is a front for extracting information and using belief as a weapon.

That’s what tickled me about the movie Heretic and the reason I think critics who wrote off Grant’s antagonist as “atheist who won’t shut up” as a shallow read. While it’s been normalized in America, the LDS Church is considered extremely weird by every existing Christian tradition outside of the United States (and Japan, *wink* for some reason *wink*).

Theologically speaking, there is very little difference between the approach that Grant takes and the approach that the founders of the LDS took (unless one believes in the authenticity of the Book of Mormon, which I personally do not). The LDS movement contains obsessives who study genetic lineages as a means of trying to “prove” that its founding myth is real. Pseudo-archaeology? Oh, you better believe that’s a Mormon thing. They’re British Israelists, dude. It’s kayfabe. Grow up.

Grant is the antagonist of the film, yet he drives the action. The missionaries are the protagonists and spend much of the film having to pretend that this useless, idiotic man with power over them is captivating and interesting. Then when he slips off screen, the viewers get the real score: this old coot is obsessed with things that these teenage girls have already processed and moved past. He’s arguing against his own imagination. After all that faux-intellectualism, the filmmaker shows the viewer that Grant has the same immature conception of Mormonism as the teenage boys from the beginning of the film, making a reference to “magic underwear.”

Heretic is a film about a boorish, verbose, poorly-read man who builds a gigantic rat trap for young women and forces other women he’s trapped to sustain the illusion. Yet, Coppins says the film doesn’t have anything to say about Mormonism. Respectfully, I disagree, and I’d go so far as to say that if one studies the Orthodox tradition, Heretic qualifies as a comedy of errors.