There’s an inherent paradox to American Christianity and it’s one that I like to explore gleefully, but not in jest. While many people have many definitions for Americanism, at its core any definition includes an inherent rejection of the monarchy and the established hierarchies of the Anglo-Catholic aristocracy. Christianity, however, is the religion of Kings. Beyond Christ’s title as the King of Kings, the role being cast to each believer is as a servant in God’s Kingdom, of which Jesus Christ was the eternal Savior. God is the King.

Americanism is about regular people overthrowing a monarchy because it sucks to live under a King. Well how the hell am I gonna believe both of those things at once? Maybe that’s why so many people here watch news about the English royals, or take guns to church. The eternal search for the Good Boss continues apace in the free world.

One of the things that I find fascinating about the Ethiopianist worldview is that it, too, is inseparable from monarchism even while its adherents pragmatically reject monarchist politics. Those in the Rastafari movement that pay attention to Ethiopian politics often are in the camp that support the restoration of the Solomonic Dynasty. However, the support is for the restoration of a constitutional monarchy. The remaining members of the Ethiopian aristocracy are not seeking a restoration of centralized Solomonic authority (not publicly, at least!).

Comparing Ethiopianism and Americanism is not as far-fetched as it may seem: the 20th century nationalistic narrative for Ethiopia was directly influenced by American intellectuals, and the March 1896 Battle of Adwa has similar symbolic meaning to July 4, 1776. The difference is that the Ethiopian aristocracy attempted to thread the needle between American revolutionary nationalism and the preserved traditions of Ethiopian / “Abyssinian” culture, including its Royalty. It had mixed results, but it didn’t fail either, evidenced by Ethiopia’s continued independence and ongoing diplomatic importance to China, the United States, Russia, France, and every other country trying to swindle East Africans out of natural resources.

Ethiopian theologian Gudina Tumsa (martyred by the Derg) observed that Christianity and nationalism could not effectively co-exist in the heart. The premise of nationalism is to create an insular nation-state, but the premise of Christendom is that borders do not exist. Tumsa was not making a casual observation but one lofted from within one of the most horrifying domestic civil conflicts of the 20th century. It’s relevant not just for my personal historical studies, but my own faith. Given the context, Tumsa was saying that Christ’s compassion should transcend one’s belief that their nation needs to “win” or claim a sense of superiority.

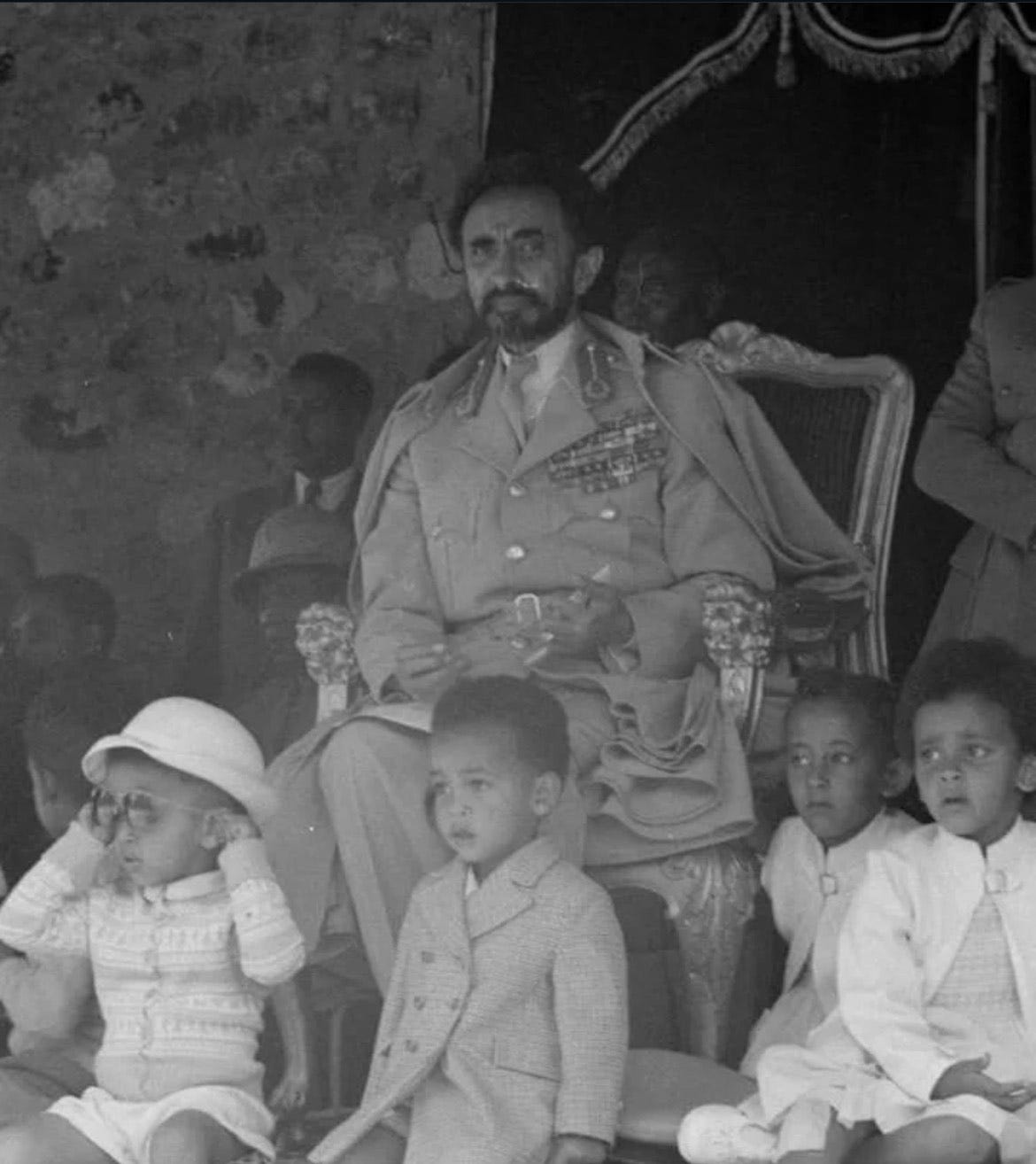

In fact, it’s one of the reasons why I struggle with / relate to Ethiopianism as an American raised in the American education system: a lot of it inherently involves some form of romanticism. Th two most extreme interpretations of Haile Selassie’s legacy in the West (a deity or an authoritarian) are themselves a form of romantic revisionism that only exist in the English language record, from my experience. Haile Selassie the revanchist and Haile Selassie the deity serve two distinct narratives for two distinct geopolitical eras between Ethiopia and the West.

Domestically, Selassie is still fairly controversial, but mostly for the same reason American historical figures are getting torn apart. The Conquering Lion of the Tribe of Judah is not alone: statues of Menelik II are also being covered in tarp in 21st century Ethiopia. The Solomonic rulers (and the Tewahedo Church associated with them) are symbols of the aristocracy and a rulership class that already inspired one populist military revolution in the 1970s (1966 E.C.). There have been a handful more since then. Based on what I’m seeing in the news, it seems likely there’s another one around the corner.

Haile Selassie cultivated a domestic nationalist narrative around breaking the chains of slavery (the emperor issued postage stamps featuring the likeness of Abraham Lincoln, which are on display at the Haile Selassie museum in Addis Ababa). However, like the founding fathers and various influential historical figures in the United States, the Ethiopian aristocracy has a mixed (and sometimes quite negative) history with imperial conquest and domestic slavery. This tarnished image is not unique to Haile Selassie, however: Tewodros II is a symbol of Ethiopian nationalism, and the Tewodros II campaign to unify a “centralized Ethiopia” in the 19th century involved territory wars. Later, Menelik II’s conquest of Harar received mixed reviews, too, if one is counting the opinions of the Muslims who came under Ethiopian administration.

In the New World, the historians pretend that thriving indigenous societies that already existed didn’t exist, and that everything we see started after the Reformation. Ethiopia, meanwhile, has a nationalistic narrative that stretches back thousands of years. To “centralize” a massive group of independent polities with inherently means that the “central authority” found a way to bring disparate independent societies to heel, either through violence or aggressive taxation. You know. Like Federalism.

However, the modern view is not as simple as “Solomonic Rulers Bad.” The Christian emperors of the Ethiopian nation reigned during a time that all of Africa was under colonial attack. I’ve spent time with Ethiopians in the diaspora who speak very poorly of Haile Selassie’s reign given the treatment of Oromo and Tigrayans. I’ve also had conversations with modern Oromo Muslims in Addis Ababa who proudly embrace iconography of Menelik II and Haile Selassie I. It’s not as simple as “Christian vs Muslim” or “Amhara vs everyone else” as is often portrayed.

The thing all seem to have in common is overriding pride in Ethiopian culture — and a subsequent limit to engagement with iconoclasm against Tewahedo — which helps to explain why even the most ardent anti-imperialist movements remaining in East Africa still embrace His Imperial Majesty. Today, with the Church still under attack by the central government, the Solomonic Dynasty is once again becoming an active and visible symbol of Ethiopian unity. The Ethiopian Nationalist narrative claims descent of rulers that stretch all the way to the time of D’mt in 8th Century BC, so the tribal politics are bound to be a little complicated!

I wasn’t around for any of it but I’ll never forget the tone of voice taken by an herbalist MMA fighter I met in Jamaica named Tony. Tony was a Muslim from Ghana on vacation after tournament in Cuba and when we were discussing our religions over coffee, I asked if he was Sufi given his love for Rastafari and ganja. He clarified that he was Sunni but that the Sunnis of Ghana “have much respect for the religion of Addis.” The man was very careful to distinguish the religion of Addis from Christendom, and to remind me that Haile Selassie did not fit a leadership mold like any I was raised with.

I don’t know about any of it because I live over here in Pittsburgh where “the monarchy” — all monarchy — sucks. We don’t like that here. That’s not coming back. Even if the Times Magazine is putting the James Dean of “Making An Ideology Out Of Only Being Friends With the Computer” in the pages. Apparently the leather jacket guy wants to bring back Kings and Queens so he can play Peter Pan forever. It’s always a leather jacket guy.

But how can a Neo-Monarchy ideologue also be pro-Americanism? It’s hard to conclude it’s because of anything other than the Christianity, and belief in Divine Provenance. Authoritarian rule is bad unless the authoritarian is Our Guy, because we can trust Our Guy. You’d have to be dumber than dogshit to believe that, just like you’d have to be an idiot to think American nationalist heroes are authentic and other nationalist heroes are corrupt demagogues and propagandists.

Despite the flaws, though, the Founding Fathers here in America and the Solomonic Dynasty iconography seem to transcend the aristocratic origins. Aristocratic opinions of the peasantry have always been bleak, but the peasantry nevertheless plucks their own heroes from the aristocracy via nationalistic narrative. Maybe it’s because they own all the land that the nation is built on, so it’s impossible to love the Kingdom without worshipping the Kings.

Was Haile Selassie the Ethiopian Abraham Lincoln, as the postage stamps suggest in the Haile Selassie Museum? I have no idea because I live in America. I know that the American in the equation, Abraham Lincoln, held some pretty ugly views about Black people, but his legacy focuses on the part where he freed the slaves. The legends of Lincoln and Selassie seem to have a lot in common in that regard, with a lot of the good work seemingly drowning out the less than stellar stuff. They “made plays” as we say in basketball. Someone has to put the ball in the damn hoop while everybody else is standing around thinking up strategies.

Sometimes the romance gets a little out of hand on the rewrite, though. Is it the shared faith of the majority that makes it seemingly impossible for anyone to permanently shed reverence for the image of kings and queens? Maybe that’s how you end up with American computer Christians reminiscing about whether monarchism would be good for America. Buddy, you oughta visit Amhara first. They don’t have any jobs that preclude being in the Sun. Better hope that carpal tunnel doesn’t start acting up during the harvest.